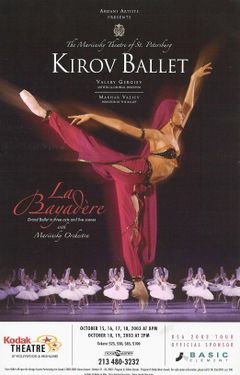

La Bayadère

| Important Ballets & *Revivals of Marius Petipa |

|---|

*Paquita (1847, *1881) |

La Bayadère (The Temple Dancer) (Russian: Баядерка - Bayaderka) is a ballet, originally staged in four acts and seven tableaux by the Ballet Master Marius Petipa to the music of Ludwig Minkus. It was first performed by the Imperial Ballet at the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, on February 4 [O.S. January 23] 1877. A scene from the ballet, known as The Kingdom of the Shades, is one of the most celebrated excerpts in all of classical ballet, and it is often extracted from the full-length work to be performed independently.

La Bayadère has been restaged and revived many times throughout its long performance history, most notably by Marius Petipa (1900, for the Imperial Ballet), Alexander Gorsky and Vasily Tikhomirov (1904 for the Ballet of the Moscow Imperial Bolshoi Theatre), Agrippina Vaganova (1932, for the Kirov Ballet), Vakhtang Chabukiani and Vladimir Ponomaryov (1941, for the Kirov Ballet), Rudolf Nureyev (1963—the scene The Kingdom of the Shades, for the Royal Ballet), Natalia Makarova (1974—the scene The Kingdom of the Shades; and 1980—full-length, for American Ballet Theatre), Rudolf Nureyev (1992, for the Paris Opera Ballet), and Sergei Vikharev (2001—in a reconstruction of Petipa's last revival of 1900).

Today, La Bayadère is presented primarily in one of two different versions—those productions derived from Vakhtang Chabukiani and Vladimir Ponomaryov's 1941 revival for the Kirov Ballet, and those productions derived from Natalia Makarova's 1980 version for American Ballet Theatre; which is itself derived from Chabukiani and Ponomarev's version.

Origins

La Bayadère was the creation of the choreographer Marius Petipa, the renowned Premier Maître de Ballet of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres, the Russian Emperor's institution of theatrical arts that included the Imperial Ballet (today the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet). The music was written by the composer Ludwig Minkus, Petipa's chief collaborator, who from 1871 until 1886 held the official post of Ballet Composer to the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres.

La Bayadère is a typical production of the period in which it was produced: extravagant tableaux interspersed with episodes on an active, melodramatic scenario which takes place in an exotic and ancient locale—the ideal vehicle for spectacular dances and mimed scenes, all set in an atmosphere consisting of lavish décor and sumptuous costumes. During the 1860s until the mid-1880s Petipa favored the subjects of his ballets to be of the romantic ballet tradition—ballets which were typically melo-dramas involving a love triangle of some sort, and usually consisting of a supernatural female creature who would embody the feminine ideal. The rather tragic scenario of La Bayadère is certainly a work that conforms to these elements.

The true origins of La Bayadère are rather obscured, and the identity of the person responsible for creating the ballet's scenario is open to debate. Typically before a new work was to have its premiere on the Imperial stage, the libretto and a list of dances were published in the newspaper, along with an article discussing its creation. In the case of La Bayadère, no author was credited when the libretto was first published in the St. Petersburg Gazette in late 1876. When Petipa revived La Bayadère in 1900, the newspaper again published the libretto, this time naming the writer/dramatist/ballet historian Sergei Khudekov as author. Petipa soon wrote a letter of correction to the newspaper's editor, stating that he alone bore responsibility for the libretto, though Khudekov did in fact contribute eight lines of stage direction in the margin. The St. Petersburg Gazette then published an apology to the Ballet Master, and named him as sole author. There is no evidence to dispute Petipa's claim of authorship, either by Khudekov or any of Petipa's contemporaries.

Petipa was not a man who had scruples about giving credit where credit was due, and when it came to work he alone was responsible for he made certain all published credits were accurate. In 1894 the Ballet Master wrote to the editor of the St. Petersburg Gazette when an article was published claiming his Le Réveil de Flore (The Awakening of Flora) was choreographed by both him and Lev Ivanov. In his letter Petipa stated that he alone was responsible for the choreography and the mise en scène, with Ivanov merely serving as an assistant in staging his dances. Nevertheless Petipa's efforts in correcting the newspaper seemed to have proved fruitless—the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet's 2007 reconstruction of Le Réveil de Flore credits both him and Ivanov with the choreography.

Possible influences

In 1839 a touring company of authentic Indian Bayadères visited Paris, and the celebrated dramatist Théophile Gautier wrote some of his most inspired pages in describing the troupe's principal dancer Amani. Years later in 1855 Gautier recorded the tragic fact that the dancer had hanged herself in a fit of depression in fog-bound London while longing for her beloved India, and as an homage to the Bayadère Gautier wrote the libretto for the ballet Sacountala, derived in part from a play by the Indian poet Kalidasa. The work was first presented in Paris on July 14, 1858 by the Ballet du Théâtre Impérial de l´Opéra (today known as the Paris Opera Ballet) in a staging by Marius Petipa's brother Lucien Petipa to the music of Ernest Reyer. This is the work that many ballet historians have cited as the true inspiration for Petipa's La Bayadère.

Another work with similar themes of exotic India that may have inspired Petipa was Filippo Taglioni's two-Act opera-ballet Le Dieu et la Bayadère, ou La Courtisane amoureuse , set to the music of Daniel Auber, and presented in Paris at the Opéra. This ballet was first presented on October 13, 1830, and was attended by a young Marius Petipa. The action of this work was fashioned by Eugene Scribe from Johann Goethe's Der Gott und die Bajadere. The work was an enormous success, and included the vocal talents of the celebrated tenor and dramatist Adolphe Nourrit, with the legendary Ballerina Marie Taglioni in the principal role of Zöloe.

Plot outline

Petipa's La Bayadère (meaning The Temple Dancer or The Temple Maiden) tells the story of the Bayadère Nikiya and the warrior Solor, who have sworn eternal fidelity to one another. The High Brahmin, however, is also in love with Nikiya and learns of her relationship with Solor. Moreover, the Rajah Dugmanta of Golconda has selected Solor to be the fiancé of his daughter Gamzatti (or Hamsatti, as she is known in the original production), and Nikiya, unaware of the arrangement, agrees to dance at the couple's betrothal celebrations.

The jealous High Brahmin—in an effort to have Solor killed and have Nikiya for himself—tells the Rajah that the warrior has already vowed love to the Bayadère over a sacred fire. But the High Brahmin's plan backfires when, rather than becoming angry with Solor, the Rajah vows that Nikiya should be the one who must die. Gamzatti, who has been eavesdropping on this exchange, summons Nikiya to the palace in an attempt to bribe the Bayadère into giving up her beloved. As their rivalry intensifies, Nikiya picks up a dagger in a fit of rage and attempts to kill Gamzatti, only to be stopped in the nick of time by Gamzatti's aya (or maid). Nikiya then flees in horror at what she had almost done. As did her father, Gamzatti vows that the Bayadère must die.

At the betrothal celebrations Nikiya performs a somber dance while playing her veena. She is then given a basket of flowers which she believes are from Solor, and so begins a frenzied and joyous dance. Little does she know that the basket is from the Rajah and Gamzatti, who have concealed beneath the flowers a venomous snake. The Bayadère then holds the basket too close and the serpent charges forth and bites her on the neck. The High Brahmin offers Nikiya an antidote to the poison, but she chooses death rather than life without her beloved Solor.

In the next scene the depressed Solor smokes opium. In his dream-like euphoria he has a vision of Nikiya's shade (or spirit) in a nirvana among the star-lit mountain peaks of the Himalayas called The Kingdom of the Shades. Here, the lovers reconcile among the supreme opulence and order of the shades of other Bayadères (in the original production of 1877 this scene took place in an illuminated enchanted palace in the sky). When Solor awakes, preparations are underway for his wedding to Gamzatti.

In the temple where the wedding is to take place the shade of Nikiya haunts Solor during his dances with Gamzatti. When the High Brahmin joins the couple's hands in marriage, the Gods take revenge for Nikiya's murder by destroying the temple and all of its occupants.

In an apotheosis the shades of both Nikiya and Solor are reunited and spirited off toward the Himalayas.

Original production

La Bayadère was created especially for the benefit performance of Ekaterina Vazem, Prima ballerina of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres. During the mid to late 19th century Russian ballet was dominated by foreign artists, though during the late 1860s through the early 1880s the theatre administration encouraged the promotion of native talent. The Russian ballerina Vazem – a terre-à-terre virtuosa – had climbed the ranks of the Imperial Ballet to become one of the company's most celebrated dancers.

The role of Solor—being almost exclusively a mimed role with no classical dances—was created by Lev Ivanov, Premier danseur of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres. Ivanov would go on to become régisseur and Second Maître de Ballet of the Imperial Theatres, as well as a noted choreographer.

Petipa's work on La Bayadère

Petipa spent almost six months staging La Bayadère, all the while mounting the work in the midst of difficult circumstances. The Director of the Imperial Theatres, the aristocrat Baron Karl Karlovich Kister, had very little sympathy for the ballet, and enforced stringent budget limitations whenever possible. At that time in Tsarist St. Petersburg the Imperial Italian Opera was in fashion far more than ballet, and as a result of enjoying the favor of the public, the troupe monopolized on rehearsal space and performance time on the stage of the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre (principle theatre of the Imperial Ballet and Opera until 1886, when the companies were transferred to the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre). This left the ballet company only two days a week in which to perform, while the Italian Opera performed six, and sometimes seven times per week. Because of this, Petipa was given only one dress rehearsal for La Bayadère, being the only time before the premiere that all of the scenes and dances were brought together on stage. During this rehearsal, Petipa clashed with the Prima ballerina Vazem over the matter of her entrance in the ballet's final Grand Pas d'action, and the Ballet Master also experienced many problems with the set designers who constructed the ballet's elaborate stage effects. Petipa was also worried that his new work would play to an empty house, as the Director Kister increased the ticket prices to be higher than that of the Italian Opera, which at that time were rather expensive. It is significant to note that the 1877 premiere of Swan Lake was being prepared in Moscow the same year as La Bayadère in St. Petersburg.

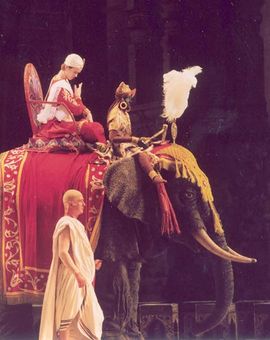

Petipa opened La Bayadère with the scene The Festival of Fire (Act I-Scene 1)—a scene in which the delicate dances of the Bayadères alternated with wild and frenzied dancing from the fakirs, who while in a state of religious intoxication jumped through a sacred fire and taunted their bodies with daggers and knives. The Betrothal Celebrations of Act II opened with the Grand Procession in honor of the Idol Badrinata, set to Minkus's grandiose march reminiscent of a scene from Verdi's Aida (for which Petipa also choreographed the dances in the Imperial Opera's production). The procession from Act II of La Bayadère consisted of thirty six entrances for 216 participants, which included the hero Solor making his entrance atop a fifteen-foot-high bejewelled prop elephant (in his 1868 grand ballet Le Roi Candaule, Petipa also included an elaborate procession in which the heroine made her entrance riding an elephant). This was followed by the Grand divertissement which consisted of dances for the slaves and the corps de ballet, as well as character dances. Among these pieces was the Danse manu, in which the Ballerina attempts to balance a waterjug on her head, all the while attempting to keep its contents from two thirsty little girls. Following the Danse manu was the Danse infernale: a character number set to Minkus's rousing drums which one critic found to be "...more of the Indians of America than those of India". After a Coda générale for all participants, there followed the celebrated Scène dansée of the heroine Nikiya, where in the original production the Ballerina began her somber performance with a prop veena to Minkus' mournful cello solo. This was followed by a frenzied coda, and the death of the heroine by the bite of a serpent.

Typically a ballet of the period had one major Pièce de résistance in the course of an evening-length production: the Grand pas. For La Bayadère, Petipa gave his audience two: the appearance of the heroine Nikiya's shade at the wedding of Solor and Gamzatti in the final act, and the vision scene known as The Kingdom of the Shades. Petipa's staged the appearance of Nikiya's shade at the wedding of Solor and Gamzatti in the context of a Grand Pas d'action, very much reminiscent of the Grand Pas de trois from Act I of Filippo Taglioni's original 1832 La Sylphide—the shade of the bayadère Nikiya is only visible to her beloved Solor during his dances with Gamzatti.

The most celebrated and enduring passage of La Bayadère was Petipa's grand vision scene known as The Kingdom of the Shades. Petipa staged this scene as a Grand pas classique, completely devoid of any dramatic action. His simple and academic choreography was to become one of his most celebrated compositions, with the Entrée of a Corps de ballet of shades (the ghosts of Hindu temple maidens) becoming perhaps his most celebrated composition of all. The Entrée was inspired by Doré's illustrations for Dante's Paradiso from The Divine Comedy, with each dancer of the thirty two strong Corps de ballet clad in white tutus with veils stretched about their arms. Each of the dancers made her entrance, one by one, down a long winding ramp from upstage right, with a simple Arabesque cambré, followed by an arching of the torso with arms in fifth position, followed by two steps forward. With the last two steps she made room for her sister shade, and the combination would continue thus in a serpentine pattern until the entire corps de ballet had filled the stage in eight rows of four. Then followed simple movements en adage to the end, where the Ballerinas split into two rows and lined opposite sides of the stage in preparation for the following dances. Petipa left this Entrée of shades free of technical complexity—the unison of the whole and the effect of the descending Ballerinas was the challenge, as a mistake from one dancer would spoil it. When Petipa first staged the scene The Kingdom of the Shades it was set in an enchanted palace in the sky on a fully-lighted stage.

Despite the ballet's setting in ancient India, Ludwig Minkus's music, even in the character numbers, made barely any gesture to traditional forms of Indian dance and music. The ballet was essentially a vision of the southern orient through 19th century European eyes. Although some sections of Minkus's score contained melodies that were reminiscent of the southern orient, his score was a definitive example of the musique dansante in vogue at that time, and did not stray at all from the usual string of lightly orchestrated melodious polkas, adagios, Viennese-style waltzes, and the like.

In that same regard Petipa's choreography contained various elements that reminded the spectator of the ballet's setting, but never once did the ballet master stray from the classical ballet canon. Petipa was not at all interested in ethnographic accuracy in any part of the ballet with regards to choreography. This was, after all, the fashion of the time, for whether a ballet was set in China, India, or the Middle East, the ballet master rarely, if ever, considered including traditional native dance forms.

The well-traveled and learned ballet historian Konstantin Skalkovsky commented in his review of the 1877 premiere La Bayadère on the work's ethnographic inaccuracies:

| “ | ... Petipa borrowed from India ... only some external features, because the dances of the opening scene, The Festival of Fire, are little similar to the dances of real Bayadères, which consist, as is well known, of some oscillations of the body and measured movements of the arms to the most doleful music. But if the dances of the Bayadères are ethnographically inaccurate, the idea of having the daughter of a Rajah to dance is in still greater disagreement with reality. According to Indian notions only courtesans can sing and dance, and every woman who would break this sacred decree would quickly be punished by contempt or caste. | ” |

The cast consisted of many of the Imperial Ballet's most esteemed artists. Aside from Vazem and Ivanov in the roles of Nikiya and Solor, the celebrated Ballerina Maria Gorshenkova performed Gamzatti, the High Brahmin by Nikolai Golts, and Dugmanta, the Rajah of Gulconda was performed by Christian Johansson. The lavish décor was designed by Mikhail Bocharov for Act I-scene 1; Matvei Shishkov for Act I-scene 2 and Act II; Ivan Andreyev for Act III-scene 1 and Act IV-scene 1; Heinrich Wagner for Act III-scene 2 The Kingdom of the Shades; and Piotr Lambin for the Act IV-scene 2 Apotheosis.

Critical response

The premiere of La Bayadère on February 5 [O.S. January 23] 1877, played to a full house at the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, and was a resounding success. At the end of the performance the choreographer Petipa, the Ballerina Vazem, and the composer Minkus were called for several times. Not since Petipa had mounted his last oriental extravaganza, Tsar Kandavl (or Le Roi Candaule) in 1868 had there been such unanimous praise from the critics and balletomanes.

Of course the audiences of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres adored melodramatic ballets, and the plot of La Bayadère ensured a number of powerful encounters: the scene of jealousy between Nikiya and Gamzatti, as well as the scene of Nikiya's rejection of the High Brahmin's declaration of love, were all praised by critics. A critic from the St. Petersburg newspaper The Theatre Echo commented positively:

| “ | Looking at the new ballet one can only be astonished at the inexhaustible imagination that (Petipa) possesses. All of the dances are distinguished by their originality and color; novelties in groupings, a wealth of invention, the intelligence of the story, and its correlation with the locale of the action – these are the principal merits of La Bayadère. | ” |

One critic hailed the work humorously as ""Giselle", east of the Suez", while another went on to comment on the mistakes made by the stage hands when presenting the "special effects" of the ballet, which apparently worked effectively only when timed correctly:

| “ | ... a mimed dialogue where (the character Nikiya) reveals a castle in the sky (to the character Solor) was not timed correctly with Mme. Vazem's gesture, and the castle, which was seen through a window, did not appear until the Danseuse had already turned away ... the final scene which included the destruction of the temple in Roller's design went quite wretchedly – the structure did not begin to collapse until long moments after the musical cue, which led to a few uneasy moments with the performers running frantically about the stage for no apparent reason. | ” |

Ekaterina Vazem's portrayal of the Bayadère Nikiya became the rage of St. Petersburg society, as she was considered by the balletomanes and critics to be the supreme ballerina of her generation. After the performance the ballerina received a diamond studded ruby brooch, along with large bouquets of flowers, one of which was from Adelina Patti, the celebrated Prima donna who at that time was engaged as guest artist with the St. Petersburg Imperial Italian Opera. A critic from The Voice had nothing but praise for Vazem's portrayal of the heroine Nikiya:

| “ | (Vazem's performance was) a miracle of the choreographic art. It is difficult to evaluate that perfection with which the benefit artist, Mme. Vazem, performed all of the new dances in her new role, both classical and character. Her incomparable talent has no peer at the present time in all Europe. She has attained such a degree of perfection that it would seem impossible to go further. | ” |

The ballet historian Vera Krosovskaya would later give an assessment of Petipa's original production of La Bayadère:

| “ | ... the cheered premiere was a point of intersection of the St. Petersburg ballet's traditions and generations of dancers ... marking the transition of the Romantic ballet transforming into Classical. | ” |

Petipa's revivals

Between the premiere and Ekaterina Vazem's farewell retirement benefit performance on January 29 [O.S. January 17] 1884, La Bayadère was performed seventy times. The ballet was not performed again until December 26 [O.S. 14 December] 1884 when it was given a minor revival by Petipa for the Ballerina Anna Johansson. Petipa left much of the ballet as it was staged originally, limiting his alterations to only the Ballerina's dances.

When Anna Johansson retired in 1886, she chose the second act for her farewell benefit performance. This was the last time any part of La Bayadère was performed before the work was taken out of the Imperial Ballet's repertory.

In late 1899, it was arranged for the Imperial Ballet's Premier danseur Pavel Gerdt to be given a benefit performance in honor of his fortieth year of artistic activity on the St. Petersburg ballet stage. Also that year, the Imperial Ballet's newly appointed Prima ballerina assoluta Mathilde Kschessinskaya showed interest in having Petipa revive La Bayadère. It was agreed that the work would be a perfect vehicle for both Gerdt and Kschessinskaya, and soon Petipa began mounting a complete revival of the work for the 1900-1901 season.

Among Petipa's most striking changes for this revival was the change of setting for the scene The Kingdom of the Shades from an enchanted castle in the sky on a fully lighted stage, to a dark rocky landscape at the peaks of the Himalayas. Petipa swelled the number of dancers in the Corps de ballet from thiry-two to forty-eight, making the illusion of descending spirits all the more effective in the famous Entrée des ombres.

Petipa also created difficult choreography for the Ballerina's variations. Kschessinskaya commented on the revival many years later:

| “ | Petipa's dances for Nikiya (in the 1900 revival) were simple while still very challenging, and I had to make certain that I was in excellent form in order to properly execute his steps. | ” |

Another important change was the interpolation of "new" variations into the final Grand Pas d'action for the principal characters. As was the custom at the time, Minkus did not compose variations for the final Grand pas d'action of La Bayadère, which were always performed ad libitum, i.e. at the dancers choice (in his original score, Minkus wrote in the margin "followed by Solor and Gamzatti's variations" after the Grand adage of the Grand Pas d'action). Typically such variations were taken from already existing ballets.

Since the fifty six year old Pavel Gerdt was unable to dance Solor's variations, the Danseur Nikolai Legat performed them in his place. For his variation in the Grand pas d'action Legat chose a Variation added by Minkus to Petipa's 1874 revival of the Taglioni/Offenbach Le Papillon. In 1941 Vakhtang Chabukiani re-choreographed this variation for himself, which is still performed today by all male dancers who perform the role of Solor in La Bayadère.

The Prima Ballerina Olga Preobrajenskaya danced the role of Gamzatti in Petipa's 1900 revival of La Bayadère, and no record exists of what variation she performed during the final Grand pas d'action. By the time La Bayadère was revived by Vakhtang Chabukiani and Vladimir Ponomaryov at the Mariinsky Theatre in 1941, the variation traditionally danced by the character Gamzatti in the Grand pas d'action was a 'Variation taken from the celebrated Pas de Vénus from Petipa's 1868 ballet Le Roi Candaule to music by Riccardo Drigo. In 1947 the Balletmaster Pyotr Gusev revised Petipa's choreography for this variation, which is still performed today.

In the original production of La Bayadère Nikiya did not dance a variation during the ballet's final Grand pas d'action. However, Mathilde Kschessinskaya commissioned the Imperial Theatre's kappelmiester Riccardo Drigo to compose a new variation for her performance. As was her preference, Drigo orchestrated the music primarily for solo harp and pizzicato. This variation became the Ballerina's legal property, as was the custom of the time, and was never again performed by anyone else.

Petipa's second revival of La Bayadère was presented on December 15 [O.S. December 3] 1900 at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, receiving a rather mixed reaction from the critics and balletomanes. One critic of the St. Petersburg Gazette stated that Petipa's choreography was "" ... perhaps more boring than long and uninteresting ... ". Nevertheless, the ballet soon became one of the great vehicles for the ballerinas of the Tsarist stage, and earned a permanent place in the repertory. La Bayadère was soon considered to be one of the supreme challenges for the danseuse to demonstrate both her technical and dramatic skills. Olga Preobrajenskaya, Vera Trefilova, Anna Pavlova (who made her last appearance with the Imperial Ballet in the role of the heroine Nikiya in 1914), Ekaterina Geltzer, Lubov Egorova, and Olga Spessivtseva, to name but a distinguished few, all triumphed in the role of Nikiya. The scene The Kingdom of the Shades became one of the ultimate tests for the corps de ballet, and many young Ballerinas made their débuts in the variations from this scene.

In March 1903, the scene The Kingdom of the Shades was performed independently for the first time during a gala performance at Peterhof Palace in honor of a state visit from Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Petipa's 1900 production was changed very little over the course of its performance history. One of the major changes made to the work came in 1914 when Nikolai Legat extended the Pas d'action de Nikiya et Solor (aka Love Duet of Nikiya and Solor) from Act I-scene 1, adding in more athletic lifts and modern partnering elements. Legat's version of this Pas is still performed today, and has widely been accepted as Petipa's choreography.

The notation of Petipa's 1900 production

As with many of the works in the repertory of the Imperial Ballet at the turn of the 20th century, Petipa's choreography for the 1900 revival of La Bayadère was documented in the method of Stepanov Choreographic Notation at some point between 1900 and 1903 by the Imperial Ballet's régisseur Nicholas Sergeyev and his team of notators. Aside from La Bayadère, the ballets which were notated included Petipa's original The Sleeping Beauty, Raymonda, and his definitive version of Giselle, as well as the 1895 Petipa/Ivanov Swan Lake, and the Petipa/Ivanov/Cecchetti Coppélia.

It was with these notations that such works as The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle, Swan Lake, and Coppelia were staged for the first time in the west by Sergeyev. Today these notations—which include many of Petipa's ballets which are no longer performed—are preserved in a collection known as the Sergeyev Collection, which is today contained in the Harvard University Library Theatre Collection.

Early "After Petipa" productions

The Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow

The first "after Petipa" production of La Bayadère was staged for the Ballet of the Moscow Imperial Bolshoi Theatre by the Danseur Vasily Tikhomirov and the Balletmaster Alexander Gorsky, premiering January 19 [O.S. January 6] 1904, with the Ballerina Adelaide Giuri as Nikiya, Tikhomirov as Solor, and Ekaterina Geltzer as Gamzatti. For this production Gorsky chose to include more ethnographically accurate costumes and choreographic elements. In the scene The Kingdom of the Shades Gorsky had clad the Ballerinas in Indian dress, rather than the traditional white tutus with veils for the arms. Gorsky's production was revived by Vasily Geltzer in 1907 and in a new production in 1917 with the ballerina Alexandra Balashova and the danseur Mikhail Mordkin in the principal roles. In 1923 La Bayadère was again revived at the Bolshoi Theatre with Vasily Tikhomirov creating a new fourth act. Ivan Smoltsov and Valentina Kudryatseva revived the work in 1940 for Marina Semyonova, being the last full-length production the Bolshoi Ballet would perform until Yuri Grigorovich mounted his production for the company in 1991.

Lopukhov's production and the loss of Act IV

With the hardships brought upon the Russian Ballet by the Russian revolution, many of the works from the repertory of the St. Petersburg Imperial Ballet left the stage forever, and those that survived were soon severely altered. La Bayadère was performed for the last time in Petipa's 1900 production in August 1916. The ballet was revived in 1920 at the former Imperial Mariinsky Theatre in a production staged by Fyodor Lopukhov especially for the Ballerina Olga Spessivtseva, with Minkus' score adapted by Boris Afanasiev.

Although the reasons have become lost to history, Lopukhov's 1920 production of La Bayadère was the first revival of the full-length work to omit the final act (Act IV; known in the original libretto as the The Wrath of the Gods). Historians have cited many possible reasons for this omission: when Petrograd was flooded in 1924 many of the sets and costumes of the works performed at the Mariinsky Theatre were destroyed, among them, the décor for Act IV of La Bayadère, and it is likely that the post-revolution St. Petersburg/Petrograd ballet did not have the funding to produce new décor. Another explanation is that the Mariinsky Theatre lacked the technical staff needed to produce the effect of the temple's destruction. A third explanation sites the fact that the Soviet regime would not have allowed the performance of a theatrical presentation that included themes of Hindu gods destroying a temple. It may very well be that all of this factored into the loss of Act IV, which would not be performed again in Petipa's design for another seventy-four years.

With the loss of Act IV, the ballet's scenario had to be modified, and so Lopukhov fashioned a short epilogue with which to end the ballet. In thi scene, the hero Solor awakes from his dream and is reunited with the Bayadère Nikiya. Lopukhov still retained its final Grand Pas d'action from Act IV, which the Ballet Master moved into the Act II Betrothal Celebrations. Since it was now taken out of its original context, Lopukhov revised Petipa's choreography and edited Minkus' music in order for it to fit with the new scenario. Petipa's Danse des fleurs de lotus from Act IV—a dance for twenty-four female students—was completely omitted.

Vaganova's revival

On December 13, 1932 the great pedagogue of the Soviet Ballet Agrippina Vaganova presented her version of La Bayadère for the Kirov Ballet (the former Imperial Ballet). Owing much of her production to Lopukhov's 1920 redaction (including his "new" ending), and never straying to far from Petipa's original design for the dances, Vaganova nevertheless revised the Ballerina's dances for her star pupil Marina Semenova, who danced Nikiya. This included triple pirouettes sur le pointe (on the toes), and fast pique turns en dehors. Although Vaganova's revival did not find a permanent place in the repertory, her modifications to the Ballerina's dances would become the standard.

The Kirov Ballet's revival of 1941

In 1940 the Kirov Ballet once again made plans to revive La Bayadère, this time in a staging by the Balletmaster Vladimir Ponomaryov and the Premier danseur Vakhtang Chabukiani. This version would be the definitive staging of La Bayadère from which nearly every subsequent production would be based.

Ponomarev and Chabukiani edited much of the ballet's incidental scenes in order to speed up the action, and either trimmed or completely omitted Petipa's original mime sequences, which by the mid 20th century were considered old fashioned by the Soviet ballet. Most of the changes were to be found in the Act II Betrothal Celebrations - Ponomarev and Chabukiani revised the choreography completely for the original Grand Pas d'action from the last act, which was transferred by Lopukhov to Act II, transforming the piece into a Grand pas classique for Solor, Gamzatti, four Ballerinas, and two Suitors. The Grand divertissement of Act II went through changes as well: the Danse des esclaves was omitted, and the two part Danse pour quatre bayadères was modified so that the second dance could be performed after the central Adage of the Grand pas classique. Another important change was made to Nikiya's final dance at the end of Act II, which Petipa had originally choreographed to be performed with a prop veena. Although the choreography was retained without change the prop veena was taken out.

Originally before the Pas de deux for the characters Nikiya and Solor in Act I, an elaborate harp cadenza would herald the beginning of a scene in which Solor watched Nikiya from afar while she played a veena in a high window of the temple. For the 1941 production this number was re-choreographed so that Nikiya would instead perform a solo to the same music while holding a water pitcher on her shoulder, a revision retained in nearly all modern productions.

Ponomarev and Chabukiani then omitted an entire sequence which took place after the High Brahmin spies on the exchange of vows between Nikiya and Solor. In the original production, this passage included a scene where Bayadères return from the temple to gather water, followed by an extended scene of Nikiya and Solor saying goodbye to one another before the High Brahmin returns to swear vengeance over the sacred fire.

Ponomarev and Chabukiani chose to include the 1900 décor for the scenes used in their production, which were restored by the designer Mikhail Shishliannikov. However an entirely new set was created for the scene The Kingdom of the Shades in Shishliannikov's design. Minkus's original music was also restored from his original hand-written manuscript, though it was properly edited and re-ordered in accordance with the new scenario and order of dances.

Unlike Fyodor Lopukhov's revival of 1920 that included a short scene in which to end the ballet, Ponomarev and Chabukiani chose to end La Bayadère with The Kingdom of the Shades. Minkus's original ending for the Grand coda of the scene The Kingdom of the Shades was altered, and the epilogue from the original apotheosis of Act IV was tacked on to the music in order to bring the ballet to a close.

The Ponomarev/Chabukiani revival of La Bayadère premiered on February 10, 1941 to a resounding success, with Natalia Dudinskaya as Nikiya and Vakhtang Chabukiani as Solor.

The choreography for the dances of Nikiya went through yet another renaissance in the hands of the great virtuosa Ballerina Dudinskaya, whose revisions to the choreography are today the standard. Although her interpretation of the tragic Nikiya was looked on as unsuitable for the stellar Ballerina, she nevertheless excelled in The Kingdom of the Shades, where Petipa's strict academic patterns prevailed. In the Variation de Nikiya (a.k.a. the Scarf Duet) she studded the choreography with multiple tours en arabesque, and included, for the first time, airy splits in her Grand jetés during the Entrée de Nikiya, all the while adding fast piqué turns in the Grand coda.

The choreography for Solor went through a renaissance as well with the great Premier danseur Chabukiani in the role. Although the dances for the role of Solor had become far more prominent since La Bayadère had been performed in Imperial Russia, Chabukiani's "new" choreography would become the standard for all proceeding male dancers. For the 1941 revival he rechoreographed Nikolai Legat's variation for Solor from the original Grand Pas d'action, and also added another variation: he arranged for Minkus's music for the second passage of the Grand coda in the scene The Kingdom of the Shades to be repeated as a solo for Solor, a tradition which is still preserved today.

In 1977, the Kirov Ballet's 1941 Ponomarev/Chabukiani production of La Bayadère was filmed and later released onto DVD/video with Gabriella Komleva as Nikiya, Tatiana Terekhova as Gamzatti, and Rejen Abdeyev as Solor.

Additional dances

The Golden Idol

In 1948 the Kirov Ballet Danseur Nikolai Zubkovsky added an exotic character variation to the Grand divertissement of Act II of La Bayadère known in Russia as Bazhok or as the Little God, or as it would later be called in the west, The Dance of the Golden Idol (in Natalia Makarova's production the role is known as The Bronze Idol).

Zubkovsky created an athletic male variation in which the dancer represents a golden statue, or idol, reminiscent of the Hindu god Shiva, thereby requiring the Danseur to be completely covered from head to toe in brazen makeup of either a bronze or gold color, with the hands at all times held in the "lotus blossom" position from traditional Indian dancing.

The music used by Zubkovsky for this variation was fashioned from the Marche persane (Persian March) composed by Ludwig Minkus for Petipa's 1874 revival of the Taglioni/Offenbach ballet Le Papillon. Though titled as a march, the piece is actually a waltz in the 5/4 time signature. Today this variation is among the most popular passages of La Bayadère with audiences.

In Makarova's version of La Bayadère this solo opens the last Act, and follows John Lanchbery's introduction. The Minkus music is presented in Lanchbery's reorchesreated version. Choreographically Makarova slightly revised Zubkovsky's original steps, but remained faithful to the basic shape of the original.

Pas de Deux of Nikiya and the Slave

In 1954 the Ballet Master and Premier danseur of the Kirov Ballet (and soon to be director of the troupe) Konstantin Sergeyev interpolated a new Pas de Deux into Act I-scene 2 of La Bayadère especially for his wife, Natalia Dudinskaya. The Pas was choreographed by Sergeyev as an exotic duet with spectacular lifts and elaborate partnering for the Bayadère Nikiya and a slave partner, with Nikiya making her entrance wrapped in a long veil.

The music used by Sergeyev for this Pas de deux is by Cesare Pugni, being an adage taken from the Act II Pas des fleurs from Jules Perrot's 1844 ballet La Esmeralda.

Early productions in the West

Anna Pavlova had intended to include an abridged version of The Kingdom of the Shades for her touring company in the 1910s, for which an adaptation of Minkus' music was prepared (whoever was responsible for this has become lost to history). But for reasons unknown the production never came to fruition (the conductor Richard Bonynge included this version of Minkus' music on his 1962 recording The Art of the Prima Ballerina, as well as on his 1994 recording of John Lanchbery's adaptation of Minkus' score for Natalia Makarova's production of La Bayadère).

Nicholas Sergeyev, the former régisseur of the Imperial Ballet, staged his own version of Petipa's The Kingdom of the Shades, under the title Songe du Rajah, for the Riga Opera Ballet of Riga, Latvia, premiering September 24, 1923. He also staged Songe du Rajah for the short-lived Russian Ballet Company in London, which premiered to great success at the Bournemouth Pavilion on March 5, 1934. Sergeyev had made plans to stage Songe du Rajah for Serge Diaghilev's original Ballets Russes in Paris for the 1929-1930 season, but the production was never realized (possibly due to Diaghilev's death in August 1929). In spite of Sergeyev's many stagings of Songe du Rajah for various European companies the work never found a permanent place in the ballet repertory, and by the 1940s was no longer performed. Today choreographic documentation of Songe du Rajah is included among the notations in the famous Sergeyev Collection.

Although La Bayadère was considered a classic in Russia, the work was almost completely unknown in the west. The first real glimpse that western audiences had of the work was when the Kirov Ballet performed The Kingdom of the Shades at the Palais Garnier in Paris on July 4, 1961, and soon this almost totally unknown piece from the Imperial Petipa repertory became the talk of the western ballet world. Two years later, Rudolf Nureyev staged the scene for the Royal Ballet, with Margot Fonteyn as Nikiya. Since the original Minkus orchestral parts were only available at that time in Soviet Russia, Nureyev called upon the Royal Opera House composer/conductor John Lanchbery to orchestrate the music from a piano reduction. The premiere was a resounding success, and is considered to be among the most important moments in the history of ballet.

The dance critic Arlene Croce commented on Petipa's The Kingdom of the Shades in her review of Makarova's staging of the scene in The New Yorker:

| “ | ... Motor impulse is basic to Petipa's exposition of movement flowing clean from its source. It flows from the simple to the complex, but we are always aware of its source, deep in the dancer's back, and of its vibration as it carries in widening arcs around the auditorium. This is dancing to be felt as well as seen, and Petipa gives it a long time to creep under our skins. Like a patient drillmaster, he opens the piece with a single, two-phrase theme in adagio tempo (arabesque cambré port de bras), repeated over and over until all the dancers have filed onto the stage. Then, at the same tempo, with the dancers facing us in columns, he produces a set of mild variations, expanding the profile of the opening image from two dimensions to three. Positions are developed naturally through the body's leverage - weight, counterweight. Diagonals are firmly expressed ... The choreography is considered to be the first expression of grand scale symphonism in dance, predating by seventeen years Ivanov's masterly designs for the definitive Swan Lake ... The subject of The Kingdom of the Shades is not really death, although everybody in it except the hero is dead. It's Elysian bliss, and its setting is eternity. The long slow repeated-arabesque sequence creates the impression of a grand crescendo that seems to annihilate all time. No reason it could not go on forever ... Ballets passed down the generations like legends, acquire patina of ritualism, but La Bayadère is a true ritual, a poem about dancing and memory and time. Each dance seems to add something new to the previous one, like a language being learned. The ballet grows heavy with this knowledge, which at the beginning had been only a primordial utterance, and in the coda it fairly bursts with articulate splendor. | ” |

Nureyev's version of The Kingdom of the Shades was also staged by Eugen Valukin for the National Ballet of Canada, premiering on March 27, 1967. The first full-length production of La Bayadère was staged by the Balletmistress Natalie Conus for the Iranian National Ballet Company in 1972, in a production based almost entirely on the 1941 Ponomarev/Chabukiani production for the Kirov Ballet. For this production Minkus' score was orchestrated from a piano reduction by Robin Barker.

Natalia Makarova's production

In 1974 Natalia Makarova mounted The Kingdom of the Shades for American Ballet Theatre in New York City, being the first staging of any part of La Bayadère in the United States. In 1980 Makarova staged her own version of the full-length work for the company, based largely on the Ponomarev/Chabukiani version she danced during her career with the Kirov Ballet. Since only about 3/4 of Minkus' original, full-length score was available outside of Soviet Russia, John Lanchbery was called upon to compose the missing sections himself, all the while re-scoring the Minkus music.

Makarova made many changes in her version of La Bayadère. Aside from the musical changes made to the first two scenes, Makarova did not deviate at all from the traditional choreography as performed at the Mariinsky Theatre, though she did omit Konstantin Sergeyev's Pas de Deux for Nikiya and the Slave and used Pugni's music for a dance for the Corps de Ballet in her new version of the last act. She shortened Act II by omitting the entire Grand divertissement (possibly because the music was not available outside of Russia at that time), with the exception of the Valse des perroquets, which John Lanchbery re-scored in the style of a grand Viennese-style waltz, and which Makarova rechoreographed as an elaborate dance for the Corps de Ballet. In light of the now shortened Act II, Makarova renamed the scene Act I-scene 3. Makarova chose to retain Zubkovsky's 1948 Dance of the Golden Idol, which she renamed The Bronze Idol, and transferred to the opening of her newly staged last act.

Due to the smaller stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in relation to that of the Mariinsky Theatre, Makarova was forced to reduce the number of the Corps de Ballet in the scene The Kingdom of the Shades from thirty-two to twenty-four. She was also obliged to modify the poses' held by the Ballerinas while they stood on the sides of the stage during the variations, due to the differences in physique of western Ballerinas to that of Russian ones (Makarova changed the original position of tendu derrière effacé, with the leg held in tendu slightly bent - for which Russian Ballerinas are famous, with their arched back, torqued hyper-extended supporting legs, and severely arched feet - to tendu derrière croisé, while still holding the leg in tendu in a slightly bent position).

Makarova's biggest change however was her staging of the long lost last act, which she set to new music by John Lanchbery, since at that time Minkus' original score was still thought to be lost. Makarova in no way tried to re-create Petipa's original design, and instead completed the original scenario with choreography of her own. Following Makarova's example, many subsequent stagings of La Bayadère would include a version of the lost last act, among them, Pyotr Gusev's version staged for the Sverdlovsk Ballet in 1984.

Makarova's production premiered on May 21, 1980 at the Metropolitan Opera House, and was even shown live on PBS during the Live from Lincoln Center broadcast. Makarova herself danced Nikiya, though she injured herself during Act I and was replaced by her under-study, the Ballerina Marianna Tcherkassky. The principal roles were danced by Anthony Dowell as Solor, Cynthia Harvey as Gamzatti, Alexander Minz as the High Brahmin, and Victor Barbee as the Rajah. The décor was designed by Pier Luigi Samaritani, with costumes by Theoni V. Aldredge. Though the reaction to her choreography for the last act was rather mixed by critics, the premiere was a colossal triumph for American Ballet Theatre, who still retain the staging in their repertory today, and have recently lavished it with new sets and costumes.

In 1989, Makarova staged her version of La Bayadère for the Royal Ballet in a totally un-changed production, including copies of Samaritani's designs for the décor, and new costumes by Yolanda Sonnabend. In 1990 her production was filmed, and later shown on PBS in 1994 (and later released onto DVD/Video), with Altynai Asylmuratova as Nikiya, Darcey Bussell as Gamzatti, and Irek Mukhamedov as Solor. Makarova has since staged her production for many companies throughout the world, including the Ballet of La Scala (who have recently filmed their production and released it onto to DVD), the Australian Ballet in 1998 and the Royal Swedish Ballet. Makarova's productions of La Bayadère always include the Samaritani designs for the décor.

In recent times Lanchbery's adaptation of Minkus' music for La Bayadère (as well as his version of Minkus' Don Quixote and Paquita) has become rather controversial, with many in the world of ballet preferring to hear the score in its original form. The noted ballet critic and historian Clement Crisp commented in 1989 that Lanchbery's orchestrations for La Bayadère are "...gratuitous burblings".

In 1983 Lanchbery conducted the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in a recording of his orchestration of Minkus's music for the scene The Kingdom of the Shades. The recording also included extracts taken from the Paquita Grand Pas Classique and the Paquita Pas de Trois. The recording was released by the label EMI onto LP and cassette.

In 1994 the conductor Richard Bonynge recorded Lanchbery's orchestration of Minkus' score for La Bayadère as prepared for American Ballet Theatre's 1980 production. The recording included an arrangement of the music for the scene The Kingdom of the Shades as utilized by Anna Pavlova's company in the 1910s. The recording was released on the label Decca Records.

Rudolf Nureyev's production

In late 1991, Rudolf Nureyev, artistic director of the Paris Opera Ballet, began making plans for a revival of the full-length La Bayadère, to be derived from the traditional Ponomarev/Chabukiani version he danced during his career with the Kirov Ballet. Nureyev enlisted the assistance of his friend and colleague Ninel Kurgapkina, former Prima Ballerina of the Kirov Ballet, to assist in staging the work.

The administration of the Paris Opéra knew that this production of La Bayadère would be Nureyev's last offering to the world, as his health was deteriorating more and more from advanced HIV disease. Because of this, the cultural administration of the Paris Opéra gave the production an enormous budget, with even more funding coming from various private donations.

Nureyev wanted to use Minkus' score in its original orchestration, which was only available at that time in Russia. In spite of his poor health Nureyev made a speedy trip to St. Petersburg to make photocopies at the Kirov/Mariinsky Library of the original orchestral parts for La Bayadère, though in his haste he accidentally copied only the bottom half of each page, which fortunately included the page numbers. He did not realize his mistake until he returned to Paris, and with the help of John Lanchbery, the score was reassembled and orchestrated as close to the original as possible. Because certain sections were not copied at all, Lanchbery was forced to compose a few transitional passages, but in the end, nearly all of the music was scored by Lanchbery in Minkus' style.

Nureyev called upon the Italian film designer Enzio Frigerio to create the décor, and broadway designer Franca Squarciapino to create the ballet's costumes. Frigerio took inspiration from the Taj Mahal and the architecture of the Ottoman Empire, as well as drawings of the original décor used for Petipa's 1877 production - Frigerio called his designs "a dream of the Orient through Eastern-European Eyes". Squarciapino's costume designs were inspired by ancient Persian and Indian paintings, with elaborate head-dresses and hats, colorful shimmering fabrics, and traditional Indian garb, with much of the materials coming from Parisian boutiques that imported directly from India.

Regarding the choreography, Nureyev left nearly all of the traditional Ponomarev/Chabukiani revisions intact, all the while retaining Zubkovsky's Dance of the Golden Idol in the Act II Grand Divertissement and Sergeyev's Pas de Deux for Nikiya and the Slave in Act I-Scene 2. Among Nureyev's revisions was a passage for the male corps de ballet in the opening of Act I-scene 2, as well as another passage in the Valse évantails from Act II. He re-ordered the variations of the Shades in Act III, putting the final variation first, and revised the choreography of the Variation de Nikiya (a.k.a. the Scarf Duet) so that Solor also performs Nikiya's movements, a change he had originally included in his 1962 staging of the The Kingdom of the Shades for the Royal Ballet. In the documentary "Dancer's Dream: La Bayadere" it is said that Nureyev considered recreating the lost fourth act, à la Makarova's production, but ultimately decided to follow the Soviet tradition and end the ballet with the scene The Kingdom of the Shades, saying that he preferred the "gentler" ending compared to the original ballet's rather violent conclusion.

Nureyev's production of La Bayadère was presented for the first time at the Palais Garnier (or the Paris Opéra) on October 8, 1992 with Isabelle Guérin as Nikiya, Laurent Hilaire as Solor, and Élisabeth Platel as Gamzatti (and was later filmed in 1994 and released onto DVD/video with the same cast). The theatre was filled with many of the most prominent people of the ballet world, along with throngs of newspaper and television reporters from around the world. The production was a resounding success, with Nureyev being honored with the prestigious Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French Minister of Culture. The premiere of Nureyev's production was a special occasion for many in the world of ballet, as only three months later he died.

The Danseur Laurent Hilaire later commented on Nureyev's revival:

| “ | ... the premiere of La Bayadère was more than a ballet for Rudolf and everybody around. This is the idea that I love about La Bayadère — that you have someone approaching death, who is dying, and instead of his death, he gives us this wonderful ballet. | ” |

The 1900 reconstruction

In 2000 the performance history of La Bayadère came full circle when the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet began mounting a reconstruction of Petipa's 1900 revival.

In order to restore Petipa's original choreography, Sergei Vikharev, the Balletmaster of the company in charge of staging the production, made use of the Stepanov Choreographic Notation from the Sergeyev Collection. The most anticipated passage of the work to be restored was the long deleted last act. This scene included the lost Danse des fleurs de lotus (Dance of the Lotus Blossoms) and Petipa's original Grand Pas d'action, which up to that point had been performed during the second act in the revised Ponomarev/Chabukiani choreography.

Among other restored passages were the Danse des esclaves from Act II, all of the original mime sequences, and Petipa's original choreography for the Danse sacrée from Act I-Scene 1. Although Natalia Dudinskaya's 1954 Pas de deux of Nikiya and the Slave was deleted, Vikharev chose to retain Nikolai Zubkovsky's 1948 character dance Bazhok (or Dance of the Golden Idol), and though it was only included for the premiere, it was later reinstated due to popular demand.

For the majority of the 20th century Minkus's original score for La Bayadère was thought to have been lost. Unbeknownst to the company, the Mariinsky Theatre Music Library had in their possession two volumes of Minkus's complete, hand-written score of 1877, as well as three manuscript rehearsal répétiteurs in arrangement for two violins, which included many notes for ballet masters and performers. Sergei Vikharev commented on the restoration of Minkus's score:

| “ | ... this is a return to the source. The true, original Minkus (score) was preserved in the theatre's archives. It was difficult to restore the score as the music had been split up. We basically had to check each hand-written page to determine the correct order, because the music had been moved around in the library so many times that if it had been reorganized once more it would have been impossible to find anything. We were fortunate in being able to restore Minkus's full score for this ballet. | ” |

The Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet's traditional 1941 Ponomareyev/Chabukiani production of La Bayadère utilized the 1900 set designs for Act I, Act II, and Act III-scene 1, designed by Orest Allegri, Adolf Kvapp and Konstantin Ivanov respectively. However the 1941 production did not utilize the Pyotr Lambin's 1900 designs for the scene The Kingdom of the Shades, and instead used a design by Mikhail Shishliannikov. For the reconstruction the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet restored Lambin's designs, as well as his designs for the last act from miniature models which had been preserved in the St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music. The scene of the destruction of the temple was restored using assemblage blueprints kept in the Russian State History Archives.

The 1900 costumes designed by Yevgeni Ponomaryov were restored from the original sketches, which were kept in the St. Petersburg State Theatre Library. Technical descriptions of the costumes of La Bayadère, housed in the Russian State History Archives, were used in the reconstruction of the costumes from the 1900 production. Where possible when selecting fabrics, the costume restoration team used those described in the archive documents. Since some of these fabrics are no longer produced today the Mariinsky Theatre's costume technicians, supervised by Tatiana Noginova, used similar materials, and strictly observed the principle of sewing by hand.

The Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet opened the 10th International Stars of the White Nights Festival with their reconstruction of La Bayadère at the Mariinsky Theatre on May 30, 2001, with Daria Pavlenko as Nikiya, Elvira Tarasova as Gamzatti, and Igor Kolb as Solor. The reconstruction received a rather mixed reaction from the St. Petersburg audience, which was largely comprised with the most prominent persons of the Russian ballet. The celebrated Ballerina of the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet Altynai Asylmuratova was seen weeping after the performance, allegedly because of her shock at seeing the ballet presented in its original form. When the company included the production on their 2003 tour, it caused a sensation around the world, particularly in New York and London. To date the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet only perform the reconstruction on special occasions.

Ekaterina Vazem on the first production of 'La Bayadère'

Here is an account by Ekaterina Vazem, Soloist of His Imperial Majesty and Prima Ballerina of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres, on the first production of La Bayadère.

| “ | My next new part was that of the Bayadère Nikiya in La Bayadère, produced by Petipa for my benefit performance at the beginning of 1877. Of all the ballets which I had the occasion to create, this was my favorite. I liked its beautiful, very theatrical scenario, its interesting, very lively dances in the most varied genres, and finally Minkus' music, which the composer managed especially well as regards melody and its coordination with the character of the scenes and dances. I associate with La Bayadère the recollection of a clash with Petipa at rehearsal ... We came to rehearsals for the last act. In it Solor is celebrating his wedding to the Princess Hamsatti, but their union is disrupted by the shade of the Bayadère Nikiya, murdered at the bride's wish so that she could not prevent them from marrying. Nikiya's intervention is expressed in the context of a Grand Pas d'action with Solor, Hamsatti, and soloists, among whom the Bayadère's shade suddenly appears, though visible only to her beloved Solor.

Petipa began to produce something absurd for my entrance as the shade, consisting of some delicate, busy little steps. Without a second thought I rejected the choreography, which was not with the music, nor did it match the general concept of the dance - for the entrance of Nikya's shade who is appearing amidst a wedding celebration, something more imposing was required than these minimally effective trifles which Petipa had thought up. Petipa was exasperated - in general the last act was not going well for him, and he wanted to finish the production of the ballet that day no matter what. He produced something else for me in haste, still less successful. Again I calmly told him that I would not dance it. At this he lost his head completely in a fit of temper: "I don' unnerstan what you need to danse?! Yew can't danse one, yew can' danse other! What kin' of talent are yew if yew can' danse noseeg?!" Without saying a word, I took my things and left rehearsal, which had to be cut short as a result. The next day, as if nothing had happened, I again took up with Petipa the matter of my entrance in the last act. It was clear that his creative imagination had quite run dry. Hurrying with the completion of the production, he announced to me: "If yew can' danse sometheeg else, then do wha' Madame Gorshenkova does." Gorshenkova, who danced the princess Hamsatti, was distinguished by her extraordinary lightness, and her entrance consisted of a series of high grand jetés from the back of the stage to the footlights. By proposing that I dance her steps Petipa wanted to "needle" me: I was an "earthly" Ballerina, a specialist in complex, virtuoso dances, and in general did not possess the ability to "fly". But I did not back down. "Fine" I answered, "but for sake of variety I will do the same steps not from the last wing but from the first wing". This was much more difficult because it was impossible to take advantage of the incline of the stage (which was raked) to increase the effect of the jumps. Petipa responded "As yew weesh Madame, as yew weesh." I must add that at preparatory rehearsals I never danced, limiting myself to approximations of my dances (or "marking") even without being dressed in ballet slippers. Such was now the case - during this rehearsal I simply walked about the stage among the dancers. The day came with the first rehearsal with the orchestra in the theatre. Here of course I had to dance. Petipa, as if wishing to relieve himself of any responsibility for my steps, said to the artists over and over again: "I don' know wha' Madame Vazem will danse, she never danse at reheasals." Waiting to make my entrance, I stood in the first wing, where a voice within me spurred me on to great deeds — I wanted to teach this conceited Frenchman a lesson and demonstrate to him clearly, right before his eyes what a Talent I truly was. My entrance came, and at the first sounds of Minkus' music I strained every muscle, while my nerves tripled my strength — I literally flew across the stage, vaulting pass the heads of the other dancers who were kneeling there in groups, crossing the stage with just three jumps and stopping firmly as if rooted to the ground. The entire company, both on stage and in the audience, broke out into a storm of applause. Petipa, who was on stage, immediately satisfied himself that his treatment of me was unjust. He came up to me and said "Madame, forgive me, I am a fool." That day word circulated about my "stunt". Everyone working in the theatre tried to get into the rehearsal of La Bayadère to see my jump. Of the premiere itself, nothing needs to be said. The reception given me from the public was magnificent. Besides the last act, we were all applauded for the scene The Kingdom of the Shades, which Petipa handled very well. Here the grouping and dances were infused with true poetry. The Balletmaster borrowed drawings and groupings from Gustave Doré's illustrations from Dante's The Divine Comedy. I had great success in this scene in the Danse du Voile to Minkus' violin solo played by Leopold Auer. The roster of principals in La Bayadère was in all respects successful: Lev Ivanov as the warrior Solor, Nikolai Golts as the High Brahmin, Christian Johansson as the Rajah Dugmanta of Golconda, Maria Gorshenkova as his daughter Hamsatti, and Pavel Gerdt in the classical dances - all contributed much to the success of La Bayadère, as did the considerable efforts of the artists Wagner, Andreyev, Shishkov, Bocharov, and especially Roller (who designed the décor), with Roller distinguishing himself as the machinist of the masterful destruction of the temple at the end of the ballet. |

” |

Gallery

|

|

Sources

- American Ballet Theatre. Program for Natalia Makarova's production of La Bayadère. Metropolitan Opera House, 2000.

- Beaumont, Cyril. Complete Book Of Ballets.

- Croce, Arlene. Review titled "Makarova's Miracle", written August 19, 1974, republished in Writing in the Dark, Dancing in 'The New Yorker' (2000) p. 57.

- Greskovic, Robert. Ballet 101.

- Guest, Ivor. CD Liner Notes. Léon Minkus, arr. John Lanchbery. La Bayadère. Richard Bonynge Cond. English Chamber Orchestra. Decca 436 917-2.

- Hall, Coryne. Imperial Dancer: Mathilde Kschessinska and the Romanovs.

- Imperial Mariinsky Theatre. Yearbook of the Imperial Theatres 1900-1901. St. Petersburg, Russian Empire. 1901.

- Kschessinskaya, Mathilde Felixovna (Princess Romanovsky-Krassinsky). Dancing in St. Petersburg - The Memoirs of Kschessinska. Trans. Arnold Haskell.

- Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet. Souvenir program for the reconstruction of Petipa's 1900 revival of La Bayadère. Mariinsky Theatre, 2001.

- Petipa, Marius. The Diaries of Marius Petipa. Trans. and Ed. Lynn Garafola. Published in Studies in Dance History. 3.1 (Spring 1992).

- Petipa, Marius. Memuary Mariusa Petipa solista ego imperatorskogo velichestva i baletmeistera imperatorskikh teatrov (The Memoirs of Marius Petipa, Soloist of His Imperial Majesty and Ballet Master of the Imperial Theatres).

- Royal Ballet. Program for Natalia Makarova's production of La Bayadère. Royal Opera House, 1990.

- Stegemann, Michael. CD Liner notes. Trans. Lionel Salter. Léon Minkus. Paquita & La Bayadère. Boris Spassov Cond. Sofia National Opera Orchestra. Capriccio 10 544.

- Vazem, Ekaterina Ottovna. Ekaterina Ottovna Vazem - Memoirs of a Ballerina of the St. Petersburg Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, 1867-1884. Trans. Roland John Wiley.

- Wiley, Roland John. Dances from Russia: An Introduction to the Sergeyev Collection Published in The Harvard Library Bulletin, 24.1 January 1976.

- Wiley, Roland John, ed. and translator. A Century of Russian Ballet: Documents and Eyewitness Accounts 1810-1910.

- Wiley, Roland John. Tchaikovsky's Ballets.

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||